In catalogo mostra “Piero Manzoni”, a cura di G. Celant, Napoli, 2007, Electa, Milano, 2007

“Poche opere d’arte del XX secolo hanno acquistato un autentico status di oggetti di culto. Merda d’artista di Piero Manzoni è una di queste (...)”.

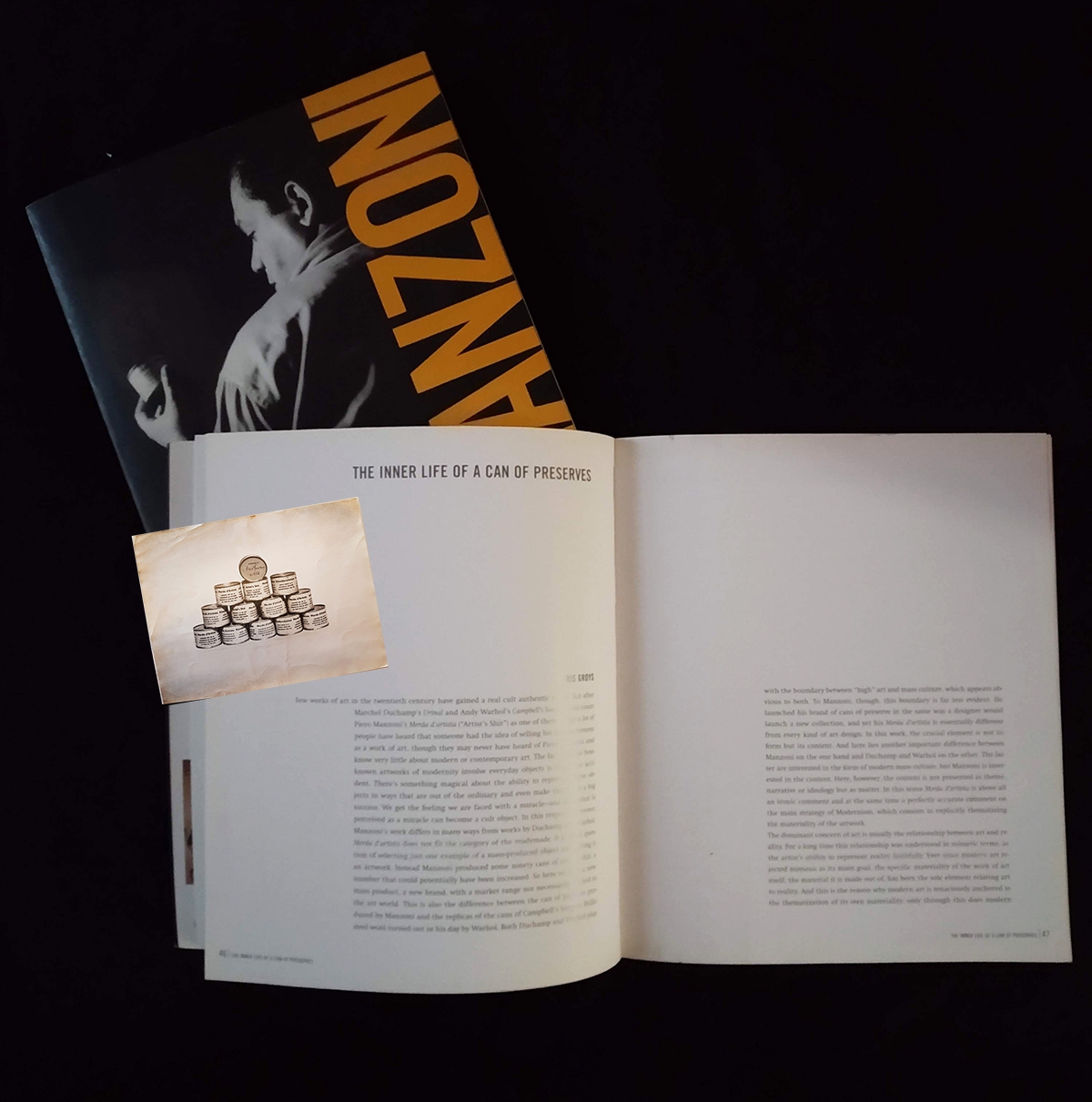

Così si apre il saggio Vita interiore della scatoletta di Boris Groys pubblicato nel catalogo della personale curata da Germano Celant presso il Museo MADRE Museo di Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina di Napoli nel 2007.

L’autore ripercorre brevemente le differenze con altre celeberrime opere-cult per poi introdurre una riflessione sul rapporto opera-realtà e quindi contenitore-contenuto, temi fondamentali affrontati nel corso di tutta la storia dell’arte. La Merda d’artista per Groys radicalizza queste tematiche perché non è dato sapere e non è importante sapere quale sia effettivamente il contenuto, anche se viene formalmente esplicitato dall’artista. Ecco come rende Manzoni sacra e inviolabile la sua opera d’arte, equiparata al corpo umano per le medesime caratteristiche. Manzoni riesce a conservare ad imperitura memoria il corpo attraverso la preservazione di una parte di esso, che questo si trovi in un museo piuttosto che in un cimitero, poco importa.

La riflessione filosofica dell’autore si conclude sottolineando l’accezione profondamente malinconica di Merda d’artista …dopotutto resta la percezione che quella “cosa” non sarà mai più quello che era prima e testimonia il destino universale della materia organica: dell’uomo infine resta qualcosa, “...non molto, ma più di niente”.

“Few works of art of the twentieth century have gained a real cult authentic status. (...) we can count Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista (Artist’s Shit) as one of them (...)”.

Thus opens the essay “The inner life of a can of preserves” by Boris Groys published in the catalog of the solo exhibition curated by Germano Celant at the MADRE Museum Donnaregina Contemporary Art Museum in Naples in 2007.

The author briefly traces the differences with other famous cult-artworks and then introduces a reflection on the relationship between work and reality and therefore container-content, both fundamental issues addressed throughout the history of art. In Groys’ idea, the Artist’s Shit radicalizes these issues because it is not known and it is not important to know what the content actually is, even if it is formally announced by the artist. This is how he makes Manzoni’s work of art sacred and inviolable, equated with the human body for the same characteristics. Manzoni manages to preserve the body for everlasting memory through the preservation of a part of it, that is in a museum rather than in a cemetery, it does not matter.

The author’s philosophical reflection concludes by underlining the profoundly melancholy meaning of the Artist’s Shit ... after all, there remains the perception that that “thing” will never be what it was before and testifies to the universal destiny of organic matter: finally something of man remains, “(...) not much, but more than nothing”.

In catalogo mostra “Piero Manzoni”, a cura di G. Celant, Napoli, 2007, Electa, Milano, 2007

“Poche opere d’arte del XX secolo hanno acquistato un autentico status di oggetti di culto. Merda d’artista di Piero Manzoni è una di queste (...)”.

Così si apre il saggio Vita interiore della scatoletta di Boris Groys pubblicato nel catalogo della personale curata da Germano Celant presso il Museo MADRE Museo di Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina di Napoli nel 2007.

L’autore ripercorre brevemente le differenze con altre celeberrime opere-cult per poi introdurre una riflessione sul rapporto opera-realtà e quindi contenitore-contenuto, temi fondamentali affrontati nel corso di tutta la storia dell’arte. La Merda d’artista per Groys radicalizza queste tematiche perché non è dato sapere e non è importante sapere quale sia effettivamente il contenuto, anche se viene formalmente esplicitato dall’artista. Ecco come rende Manzoni sacra e inviolabile la sua opera d’arte, equiparata al corpo umano per le medesime caratteristiche. Manzoni riesce a conservare ad imperitura memoria il corpo attraverso la preservazione di una parte di esso, che questo si trovi in un museo piuttosto che in un cimitero, poco importa.

La riflessione filosofica dell’autore si conclude sottolineando l’accezione profondamente malinconica di Merda d’artista …dopotutto resta la percezione che quella “cosa” non sarà mai più quello che era prima e testimonia il destino universale della materia organica: dell’uomo infine resta qualcosa, “...non molto, ma più di niente”.

“Few works of art of the twentieth century have gained a real cult authentic status. (...) we can count Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista (Artist’s Shit) as one of them (...)”.

Thus opens the essay “The inner life of a can of preserves” by Boris Groys published in the catalog of the solo exhibition curated by Germano Celant at the MADRE Museum Donnaregina Contemporary Art Museum in Naples in 2007.

The author briefly traces the differences with other famous cult-artworks and then introduces a reflection on the relationship between work and reality and therefore container-content, both fundamental issues addressed throughout the history of art. In Groys’ idea, the Artist’s Shit radicalizes these issues because it is not known and it is not important to know what the content actually is, even if it is formally announced by the artist. This is how he makes Manzoni’s work of art sacred and inviolable, equated with the human body for the same characteristics. Manzoni manages to preserve the body for everlasting memory through the preservation of a part of it, that is in a museum rather than in a cemetery, it does not matter.

The author’s philosophical reflection concludes by underlining the profoundly melancholy meaning of the Artist’s Shit ... after all, there remains the perception that that “thing” will never be what it was before and testifies to the universal destiny of organic matter: finally something of man remains, “(...) not much, but more than nothing”.

© Fondazione Piero Manzoni - Foto A. Osio

Social

Contatti

merdadartistaofficial@gmail.com